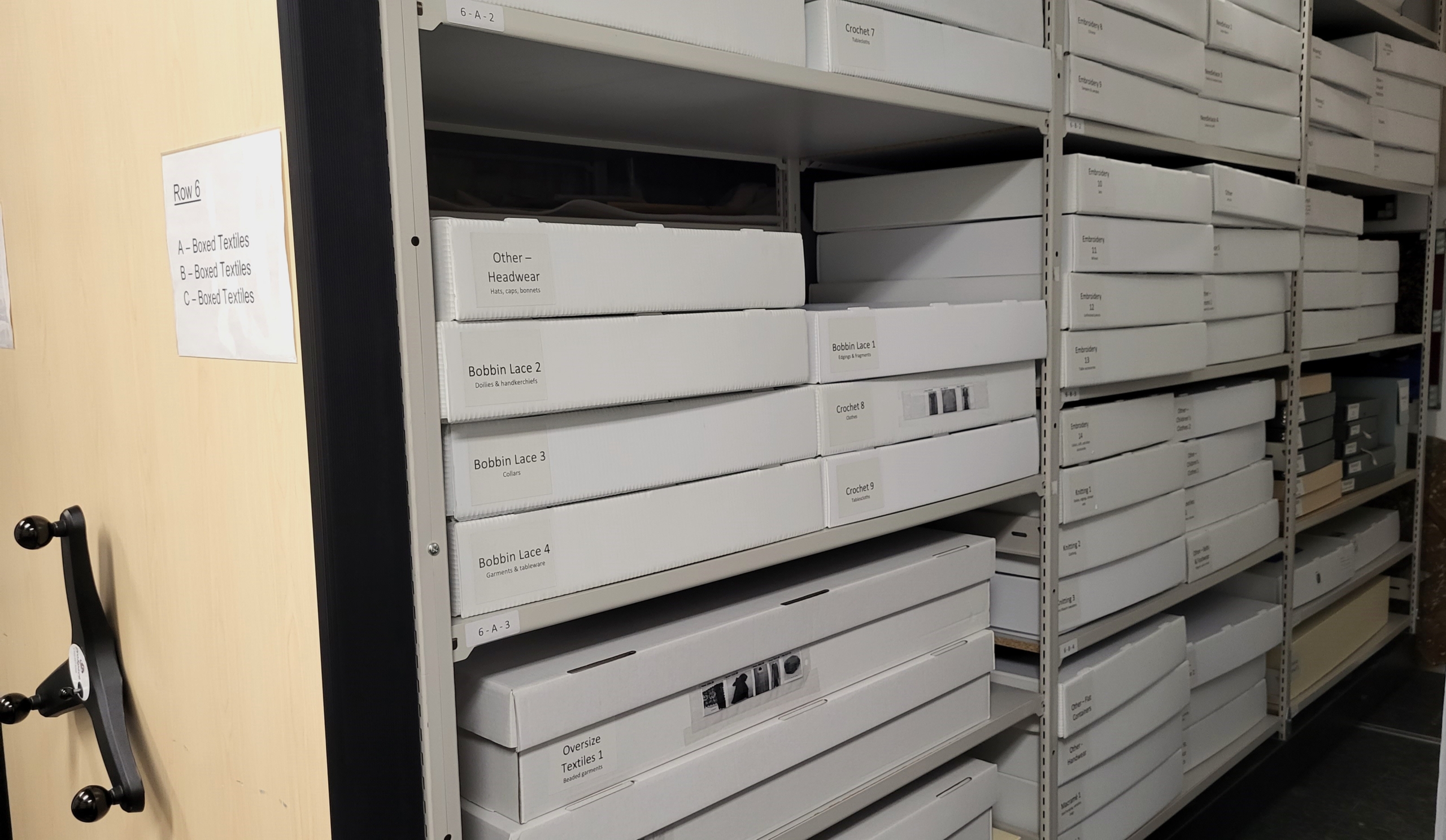

In a 10,000-object collection uniformity is an absolute necessity for providing adequate documentation and care for museum objects. Without these, our ability to retrieve information or even objects is greatly hampered. In a collection like MCML’s these pre-existing issues take on a whole new meaning when considering the uniqueness of the objects collected. The way MCML organizes its needlecraft collection in particular is fascinating to me. There are two functions I would like to share with you; vocabulary and categorization.

Part 1: Vocabulary

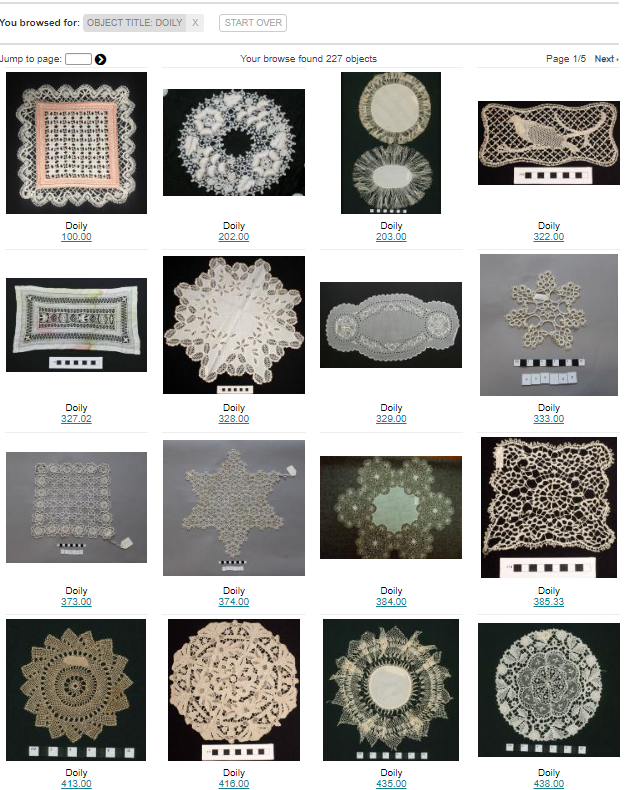

What makes a doily a doily? The size, shape, material, craft technique, or its use? Luckily for us, there are nomenclature systems that are built by and for museums to standardize the naming of museum objects. This system was started by Robert G. Chenhall in 1978 and has continued to expand since.

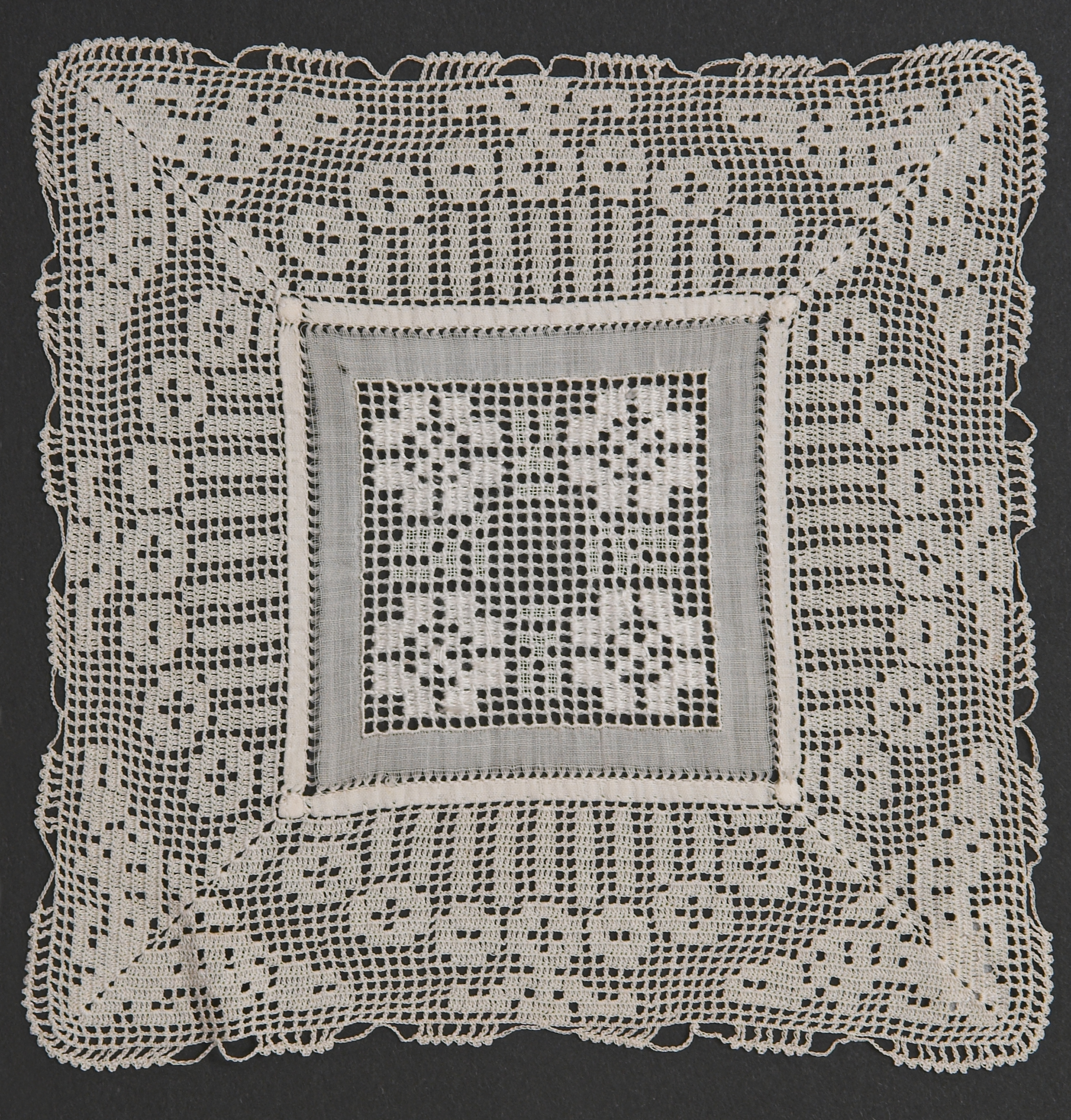

In the broad strokes, it works through a hierarchy of definitions. So for example a doily lands under the following categories; All categories → Category 02: Furnishings → Household Accessories → Furniture Coverings → Doily. From there they define doilies as “A small, decorative mat made of lace, crocheted fabric, plastic, or paper. It is usually placed under such objects as a vase or a flower pot. Used to protect an underlying surface, such as a table. Also used for decoration.”

This definition is generally a good place to start, but when categorizing such a wide variety of objects the answer is rarely so simple! The definition does not include doilies’ historic uses in binding flowers, or in food service presentation. According to the definition, a doily can be any shape, but it must be small. How large until it becomes a tablecloth; how small until it becomes a coaster? If there are an equal number of identical doilies are they then placemats?

Caption: a snapshot from MCML’s database showing a variety of doilies

Chenhall has also given us a list of materials but can a museum that specializes in craft really put a limit on acceptable techniques? This definition does not encompass, embroideries, weavings, rug hooking, or beaded pieces. What about its use, should the original owner’s use of the item affect its classification once it becomes a part of a collection?

The on-the-ground solution is to consider objects on a case-by-case basis using the methods discussed above. When this method doesn’t produce a clear answer MCML’s more experienced team members may be able to identify objects based on the placement of motifs, stains and wear. Finally, the nomenclature system is not perfect and does not include every item known to humans.

Remember that for our purpose we’re only considering doilies but these questions affect all 10,000 collection items. The application of this facilitates our ability to search the collection, use, and share items with different museums and the public. It affects our ability to research, manage the collection, plan exhibitions, and it impacts the collecting practices of the institution. It is a worthwhile endeavor to interrogate the question “what makes a doily a doily” because it enables us to get it right consistently.

Part 2: Categorization

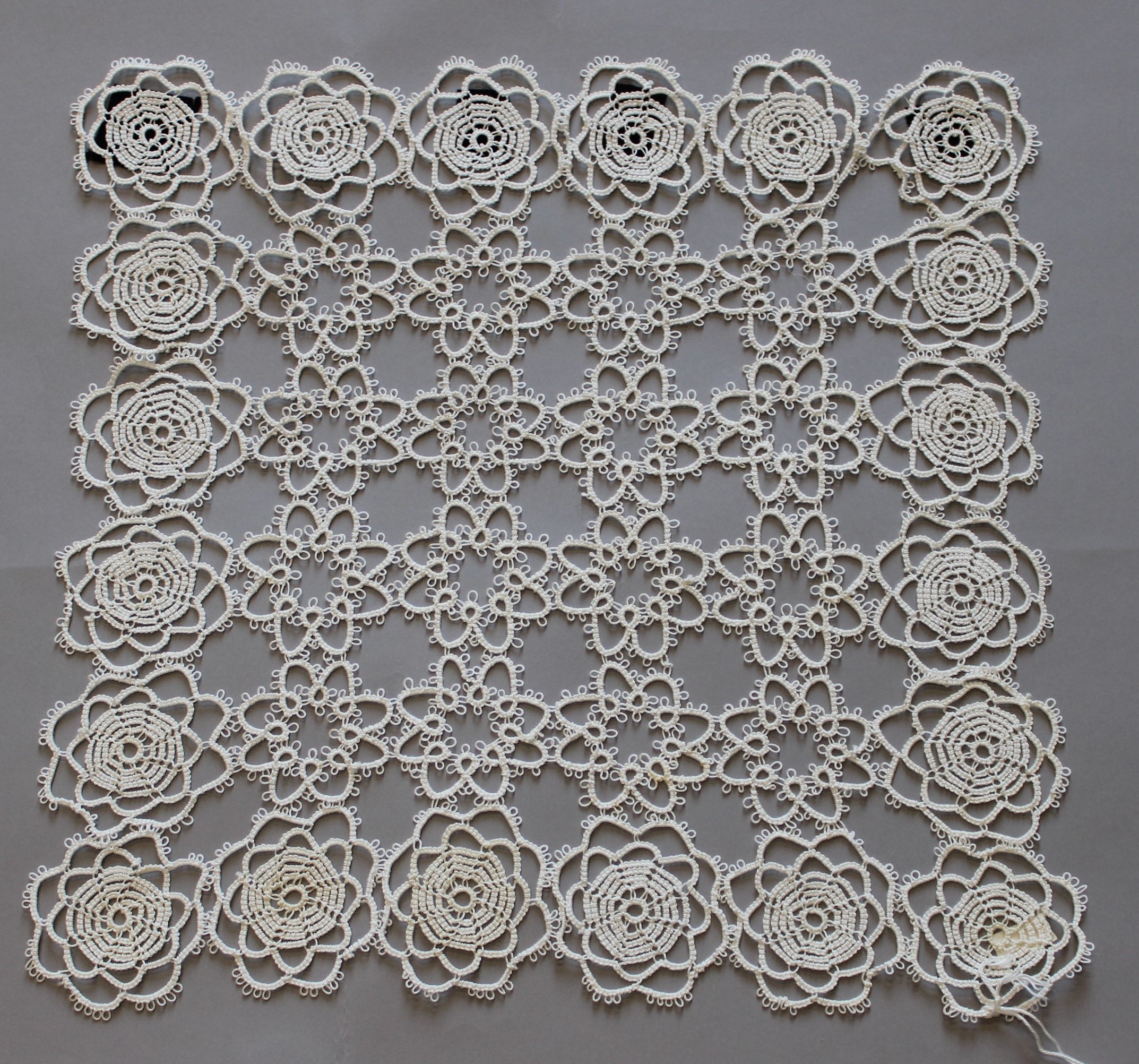

An essential function of any museum’s database is the ability to categorize and subdivide. Whether that be by subject matter, the field of study, color, culture of origin, etc, etc. Because MCML is unique in Canada, a tailor-made value list exists in our collection to organize objects by craft. Now this may seem like an open and shut case, after all, it should be fairly easy to identify craft techniques. I ask you, of the 5 doilies in the image below which one is lace?

This is a trick question they all both are and are not laces. There are two things we need to consider here; lace as a descriptor and lace as a crafting technique. As a descriptor lace is a fine openwork length of fabric. You could describe the doilies or anything with a similar openwork pattern as lacey, and subjectively you would be right. Not because that item is lace but because of its resemblance. However, when considering lace as a craft, non of the doilies actually represent a lacemaking technique.

Lace in its “purist” sense can be divided into two categories, needlelace and bobbin lace. These refer only to the tools and techniques used, not the regional styles. For needlelace, the equipment includes a needle, thread, and scissors that are used to create thousands of small stitches to form the lace itself. Bobbin lace requires more equipment; a lace pillow, bobbins, pins, thread, scissors, and possibly a pattern. It is made by twisting threads, these threads are wound onto bobbins to better manage them. Note that these two techniques require the lacemaker to make a piece of fabric from thread only.

MCML’s categorization differs from most as it purposely excludes cutwork (fig 4) and drawn thread work (fig 5) from lace. Unlike the needle and bobbin lace, both cutwork and drawn thread requires the removal of sections from existing fabric. For cutwork, the sections that have been cut out are then reinforced or filled with embroidery. In the same vein drawn thread requires the removal of threads from the warp and/or the weft of a piece of fabric. They begin with an existing piece of fabric and remove sections to create openwork.

This “purist” view of lace also excludes crochet lace (fig 2), knit lace (fig 3), and tatting (fig 1). Though all three techniques do create a piece of fabric that can be described as lace they are separate and unique craft techniques. Therefore, the end product of crochet lace is best categorized as crochet.

Museum educators are constantly balancing these competing classifications, do we present an object as it would be understood by a broad audience? Or do we use the time we have with our audience to interrogate the meaning of lace in order to present the “correct” museum classification?

The stakes of this example are minimal; if we present Irish lace as lace and not a combination of crochet lace and cutwork we’re really only risking annoying a handful of hobbyists. But like in part one these issues with categorization and terminology extend to all museums and all items in museum collections. These systems hold immense power over how objects, historical events, and even cultures are presented and are subject to the biases of their creators.

Caption: Manitoba Craft Museum and Library’s textile storage

Written by Sonia Gaiess, MCML Collections Management Assistant 2022-2023.

Funding for this blog post was provided in part by the Heritage Grants Program (Province of Manitoba) and the Young Canada Works Program (Government of Canada – Canadian Heritage).